Our History

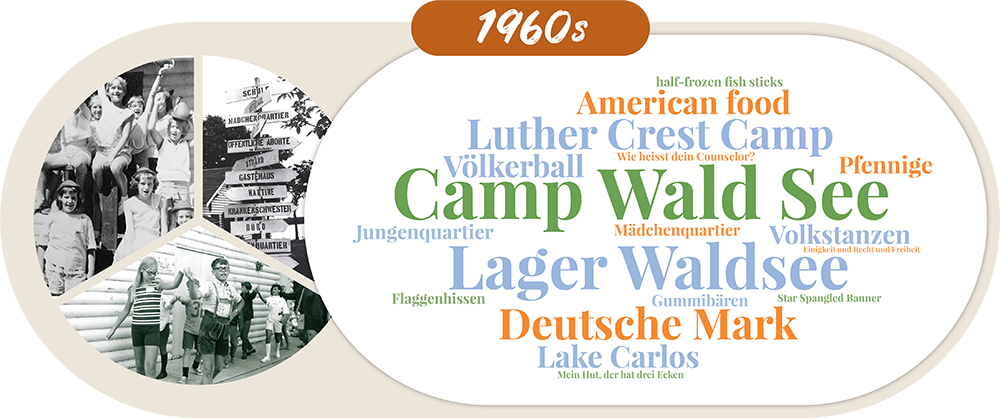

1960s

One April day in 1960, while fishing on the majestic Lake of the Woods in northern Minnesota, Gerhard Haukebo turned to his companion Erhard Friedrichsmeyer and said, “Why not start a camp for kids and teach them German? Let them have fun while they learn and put the learning of language in a natural setting.” Concordia College, where both Haukebo and Friedrichsmeyer were on the faculty, undertook the project. They named the camp after the grand lake where the idea was spawned — Lake of the Woods, or Waldsee. In 1961 Camp Waldsee’s first two-week session began at Luther Crest Camp, near Alexandria, Minnesota. Friedrichsmeyer was the camp dean, and Haukebo was the administrator. They were joined by eight counselors, a nurse, and 72 participants. Tuition was $75.

Friedrichsmeyer describes the origins of our village, and what was to become Concordia Language Villages, first-hand:

“From Aug. 20 to Sept. 2, 1961, a German language camp, as a project of Concordia College Language Camps, was held for 10- to 12-year-olds at Lake Carlos in Alexandria, Minnesota. The idea originated with Gerhard Haukebo, assistant professor of elementary education at Concordia College, Moorhead, Minnesota. While he served as a principal in a high school for army dependents in Germany, Professor Haukebo noticed how the quality of learning was greatly improved when the children could learn a foreign language in a native environment. During my own period of teaching at Concordia College in 1959, I myself organized German classes for a hundred children. Our mutual interests prompted us to co-operate in organizing 'Camp Waldsee.'

We began to work under the guiding principle that the camp should be for the children the next best thing to being in Germany. Prior to opening the camp, the staff worked feverishly to create, physically, first of all, a German atmosphere in the camp. Some 60 signs were painted and put up to designate all locations and facilities in German. If one wanted to get around in the camp, one simply had to know what "Parkplatz," "Fußballplatz," "Speisesaal," "Schule," "Aborte," "Mädchenquartier," "Jungenquartier" and, of course, "Krankenschwester" meant. Numerous travel posters were displayed. A "Kiosk" was set up featuring 20 varieties of German candy and records. "Lederhosen," "Dirndls" and other typically German items could be bought by the children. All purchases were made with German money which was available at the "Wechselstube." A public address system was put into every cabin as well as on the grounds for playing German music, for announcements, and informal language instruction. For instance, the children would hear at reveille: "Guten Morgen, Kinder. Steht auf. Hans steht auf. Wir stehen auf," etc. Each drill pattern was used repeatedly til the children were well familiar with it. If the pattern drill did not succeed in getting the campers out of bed, Bavarian band music, which followed the drill, usually succeeded.

The actual language instruction at our camp consisted of two formal class sessions a day, attended by all 75 participants. These mass sessions, in which new material was introduced, were followed by two group sessions a day. Our eight counselors, six of whom were graduate students in German, three of whom were native speakers, conducted the group sessions, drilling and adding to the material presented in the mass sessions. Each group met in a different spot on the camp grounds. In the mass sessions instruction had to be quite impersonal. At the group meetings, however, each child would receive personal attention. Inge, Heidi or Gretchen — the children knew one another only by their German names — would have a chance to practice those bothersome "ich" and "ach" sounds or name the items of their own clothing and the color of these items. In a geography lesson attended by all campers everyone would hear about Germany as a whole. At the group meetings the girls from "Schweiz," our southernmost cabin, or the boys from "Sachsen," which was of course farther north in our miniature Germany, would find out about their own province. The boys from "Westfalen" would have gladly traded their "Pumpernickel" for the "Mercedes" which the girls from "Schwaben" featured as their claim to fame.

The shift to German as the classroom language was gradual. Insistence on the exclusive use of German from the very beginning would have unduly impeded communication between student and teacher. After one week, however, no English was spoken in the classroom. Instruction was limited to two sentence types in the present tense, the actor-action type (Hans spielt Fußball) and the equational type (Der Kaffee ist heiß) with a variety of adverbs and prepositional phrases. The children learned to handle these types spontaneously in variations, including question and command patterns. In addition they learned about fifty fixed phrases (Es tut mir leid. Wie geht's?). Approximately two hundred vocabulary items were taught in the phrases. If this does not seem to be much, it is definitely enough material for all sounds and principal sound configurations to appear. Our main linguistic goal was thorough mastery of these patterns.

During the activities such as "Völkerball," "Reiterkampf," "Tauziehen" or "Schnitzeljagd" language instruction was less rigorously pursued. We did not insist on responses in German. The counselors, however, spoke only in German with one another. The instructions for games were given in German, if at all possible, and the children therefore quickly learned to pay attention when they heard German. After a few days of camp one ten year old girl asked excitedly, after having listened to my three year old daughter's chatter in German: "How long has she been taking German?" After a week and a half the children not only knew that they were hearing German when the staff spoke, but they could also understand some of it. As we were coming from the "Fußballplatz" in the heat of the day, the staff discussed in German an extra swimming hour before dinner. To our amazement one child all at once shouted: "Say, they'll let us go swimming before dinner today." We were even happier about this shout than the children were about the swimming hour.

Naturally, general camp activities are much the same everywhere. But whenever possible our activities had a German coloring. The music by our oompah band was German. Our little play was "Rotkäppchen," in German. The ghost stories at the camp fire were German ghost stories. The songs there and on the hikes were German songs. The favorite by far was "Ade zur guten Nacht." Each evening at bedtime the record was played over the P.A. system and the children in each cabin joined in as the lights went out in the camp. There was a German prayer at the table and whenever there was a birthday the children would stage a "Dreimal hoch," throwing the "Geburtstagskind" high in the air. Among other activities rarely found in this country, soccer, for example, caught on so well that the boys' all-stars almost licked the counselors. Our hope that the children would accept this exposure to things German was quite unexpectedly rewarded when one evening at one of the German movies, about an equestrian competition, our boys and girls broke out in wild cheers whenever a German horse would ride the course. It should perhaps be mentioned here that only very few children were of German descent.

We fostered a spirit of competition in learning, boys versus girls, cabin versus cabin. After one week a test was given in which all signs had to be known and pronounced (the only written forms that were introduced) and the children had to know some things about the regions which all cabins represented. After passing, the children were declared "Waldseebürger" and given a camp emblem button and an Alpine hat which they wore very proudly. The final examination, a combination treasure hunt and test, with German directions, pass words, and test stations in the woods, provided us with an overall view of the campers' progress, as well as with an indirect critique of our teaching.

Perhaps the most rewarding aspect of the camp is the favorable reaction of children, parents, and the press. Each camper is permitted to return once more and, at the closing of the session, 30% of the campers had already signed up to return. By October 1961, our planned maximum of 75 had to be increased to a maximum of 125 campers. Parents showed themselves quite concerned about continuation of instruction in their hometown schools. Campers reported that they were asked by a number of schools to go from class to class to tell about "Waldsee." Several principals have reported that they are planning to institute foreign language programs in their schools because of the favorable reaction on the part of children and parents. In spite of very limited advertising, we had 175 visitors at the camp, in addition to an entire school board from a Minnesota town. A group of community leaders from Montana approached us to organize a camp there in 1962. The three papers that covered the camp, the "Minneapolis Sunday Tribune" in a color coverage, reacted quite favorably. KCMT Television, Alexandria, Minnesota, compiled a 30 minute documentary film which is available on loan, free of charge.

It became evident to us that the language camp for children is a means of instruction superior to the classroom since it forms an emotional attachment to the new language. In a camp, instruction can take place in an atmosphere much more representative of the country whose language is learned. Furthermore, language instruction is linked with all those experiences which make camps popular with children. The student who has participated in a language camp may find this experience so enjoyable that it becomes a determining factor in the selection of courses in high school or college. Why should our field not compete with others in attracting students with all the means at our disposal? The language camp for children is one of them.”

Lee Mosher, one of the original campers from 1961: “I remember learning wonderful stories from Germany, learning to sing many German songs, and a boy from Detroit Lakes with a fondness for raspberry syrup. Camp Wald See showed how learning could be fun.”